SOCIAL MEDIA NEWS

How to spot health misinformation

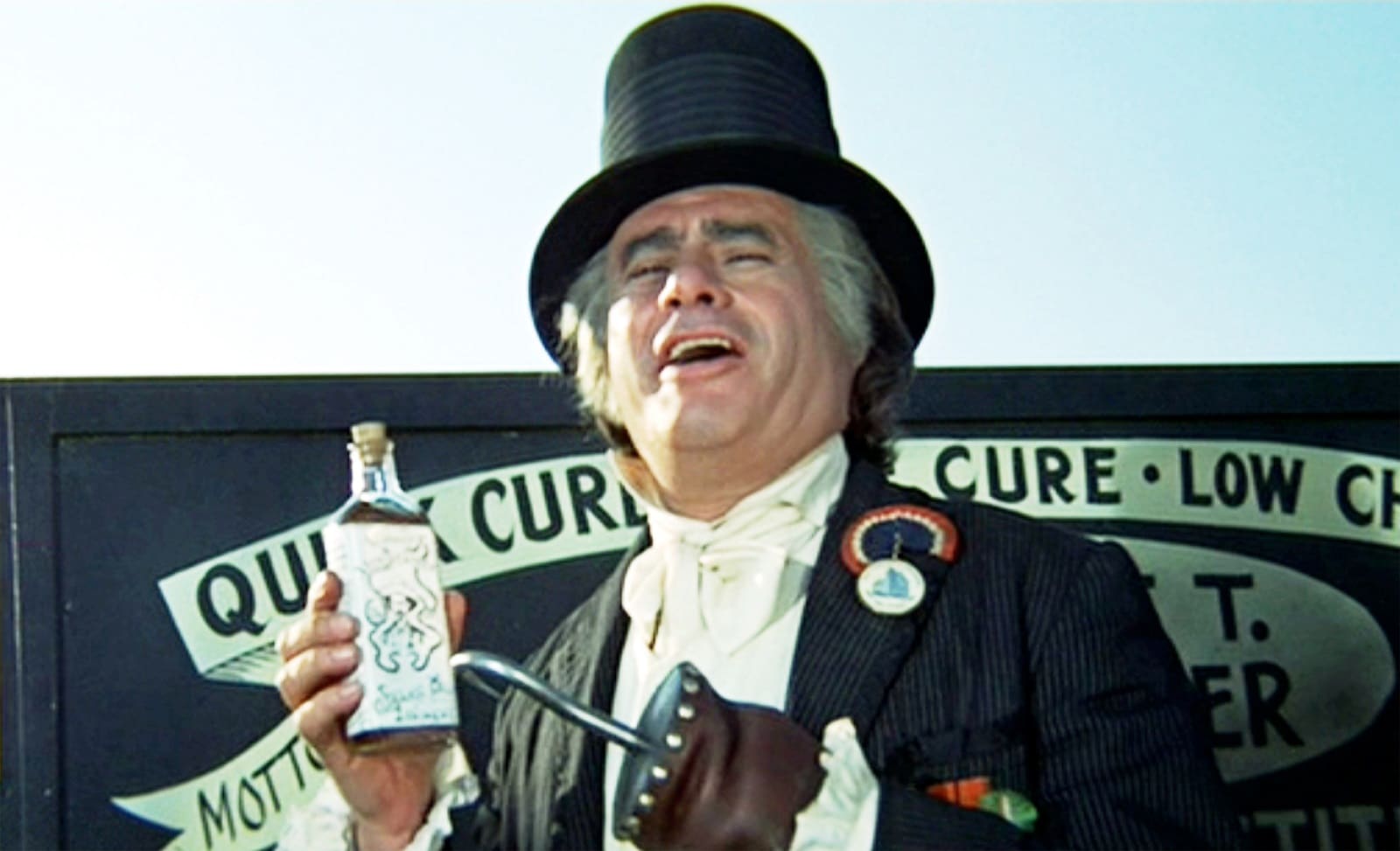

Actor Martin Balsam plays a traveling snake oil salesman in the 1970 movie, “Little Big Man”CBS Photo Archive/GettyWith more people than ever turning to the internet as their primary news source, and companies such as Facebook doing so little to curate its content, misinformation is flourishing.As Carl Bergstrom, a University of Washington researcher and the co-author of the misinformation guide “Calling Bulls—” has explained, the goal of the entities responsible for misinformation is to generate mass confusion. That leaves charlatans with the opportunity to sell phony cures or to sow division among the public for political purposes. CNBC spoke to a variety of misinformation experts and doctors for their tips on rooting out health misinformation.Here’s what they had to say:Watch out for highly exaggerated languageTim Caulfield, a professor of law at the University of Alberta, studies health misinformation and in particular the role that celebrities and influencers play in spreading it. One of his top tips is to be skeptical of any really outlandish claims.If you spot an article on sites such as Facebook or Instagram claiming that some new scientific research is a “breakthrough,” “revolutionary,” or “the first ever,” that’s often a red flag, depending on the news source. Scientific breakthroughs are possible, but they do not happen often — and when they do, it’ll be a major news event.”Be skeptical when any extraordinary claim is made when it comes to science,” said Caulfield. “It’s vanishingly rare to have any of these things play out.” Be particularly wary of any organization purporting to have a vaccine or proven cure for the coronavirus at this time. It is too soon to know when we might have a drug to treat the virus. We should know more in the next few months as we start to get the results of many ongoing trials. So for now, a claim like that is likely a charlatan trying to sell you something by tapping into your fears about the virus. Look for conspiracy anglesDr. Zubin Damania, a physician and science communicator known for his medical-themed rap videos, has kept a close eye on misinformation during the pandemic. He’s spotted a lot of content purporting to expose some kind of conspiracy about the coronavirus, such as the “Plandemic” video that went viral last month. Among the false claims included in the video without evidence: The coronavirus was manipulated in a lab, and masks will lead to people injecting themselves with coronavirus from their own breath. Damania said to be wary of any kind of language like, “here’s a reason why the authorities kept this quiet,” or “this is a secret they didn’t want you to know.”One useful exercise he recommends is to think through the so-called revelation and really question whether it makes sense. Often there are clear gaps in the logic.He also suggests looking out for experts who have no prior expertise in the field, or whose past work has been discredited. In the case of “Plandemic,” one of the “experts” interviewed, Judy Mikovits, previously published research into chronic fatigue syndrome that was later discredited.Is the study peer-reviewed?In the rush to bring new information to the public during the pandemic, there’s been a glut of seemingly authoritative research papers published on “preprint servers,” including bioRxiv and Medrxiv.These sites feature research that has not yet been peer reviewed — or vetted by an independent panel of experts. Without peer review, it’s hard to verify the quality of the work and the methodologies used. The organizations behind the servers are improving their screening practices to ensure that there are greater controls about the information that gets posted. In particular, they’ve been on the hunt for papers that could promote conspiracy theories, according to Nature News. But it’s still worth having some degree of skepticism about research that has not yet been properly vetted.If you’re in doubt, check to see what scientific experts are saying about the study on social media. There have been many cases during the pandemic where notable epidemiologists such as Harvard University’s Marc Lipsitch have called out problems they see in real time. When it comes to scientific studies, Caulfield has his own checklist he reviews before forming any conclusions. He notes that it’s worth considering any biases of the researchers, including where the funding for the study came from. He adds that it’s worth knowing whether the research involved an animal study or a human study — these are far from the same thing.The sample size matters, according to Caulfield, as well as the methods used by the scientists to recruit people to the study. Solely relying on Facebook, for instance, can result in biases in part because some groups are far less likely to use social media than others. Use of emotional languageAre you feeling riled up or deeply fearful just reading the content? Sometimes, that’s a totally appropriate way to feel, if the story is presenting harrowing facts. But it’s also a strategy to tap into people’s emotions in order to generate publicity. Caulfield is particularly skeptical of reports that use divisive language that is clearly trying to leverage ideology, frustration or fear, versus simply presenting the facts. Sometimes, this kind of misinformation will be used when the author’s ultimate goal is to try to sell something. So be particularly wary if the piece of content is pushing a brand or product.Read beyond the headlineIf the source of information is a news source you don’t recognize or it sounds similar to one you follow but doesn’t seem right, dig a little deeper.During the pandemic, with the handle @BBCNewsTonight to spread fake news about the coronavirus (the real handle is @BBCNews). That account spread many lies, including that the actor Daniel Radcliffe had tested positive for the virus. Another piece of advice from University of Southern California science communication lecturer Sarah Mojarad is to read full stories. Don’t rely on the headline alone, because the content sometimes won’t match up. It’s also worth looking up the author’s biography to see if they’re legitimate, as well as the date stamp, as social media will often resurrect outdated stories. Techniques such as using ALL CAPS, too many banner ads, a lack of links or quotes, clearly Photoshopped pictures and pushy messages to re-share the content are also telltale signs. Similarly, keep an eye out for bad grammar or egregious spelling errors. Mainstream outlets will slip up from time to time, but most have copy editors on staff to root out the majority of the mistakes. Perpetuators of misinformation often do not. When in doubt about whether a site or a claim is real, there are resources available such as FactCheck.org or APFactCheck. It’s also always worth seeing if the information is corroborated in mainstream news sources. For health information, authoritative sites to check include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Source link