SOCIAL MEDIA NEWS

Behind the Facebook-fueled rise of The Epoch Times

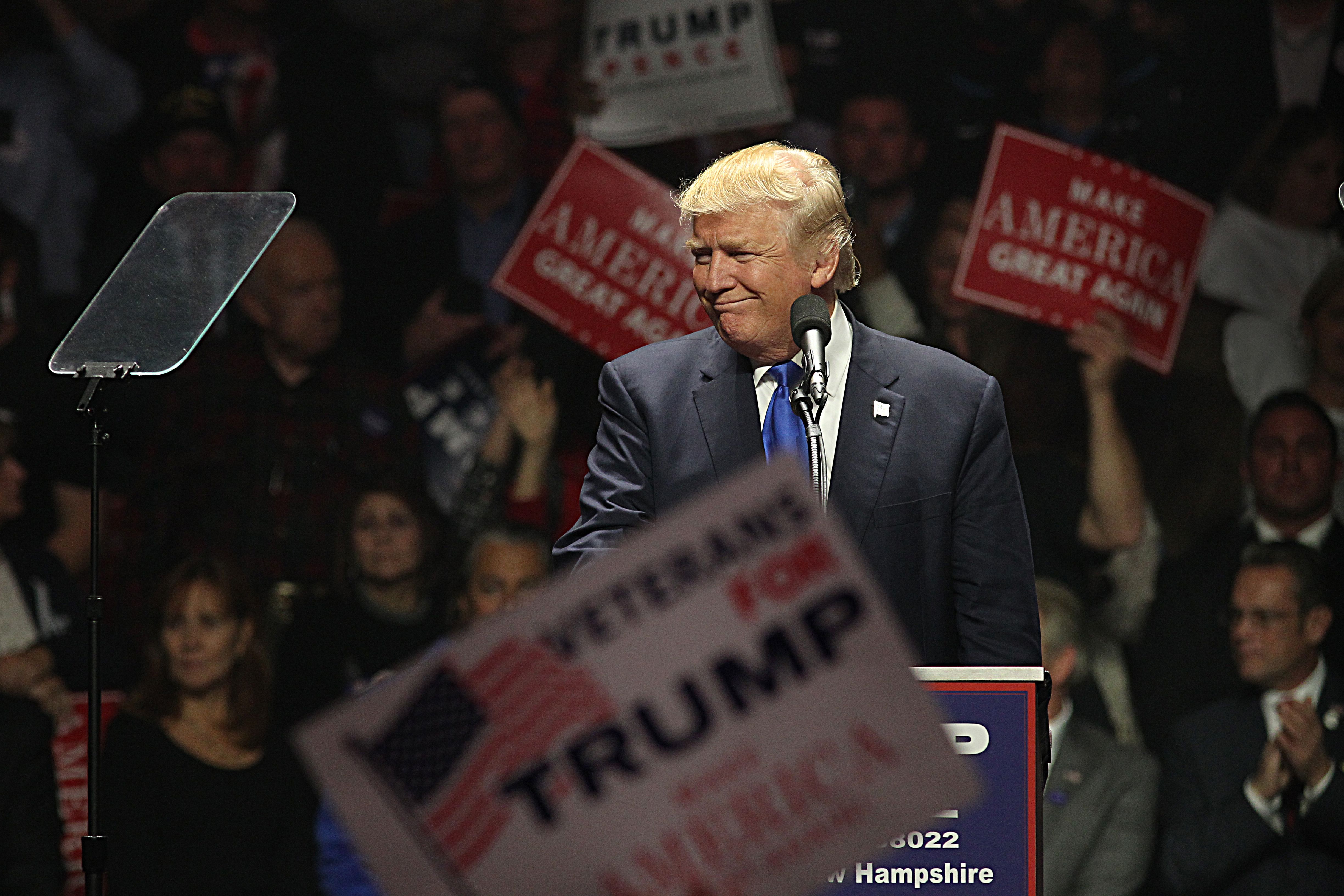

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks at a rally at SNHU Arena in Manchester, NH, on Nov. 7, 2016, the night before election day.

Suzanne Kreiter | Boston Globe | Getty Images

By the numbers, there is no bigger advocate of President Donald Trump on Facebook than The Epoch Times.

The small New York-based nonprofit news outlet has spent more than $1.5 million on about 11,000 pro-Trump advertisements in the last six months, according to data from Facebook’s advertising archive — more than any organization outside of the Trump campaign itself, and more than most Democratic presidential candidates have spent on their own campaigns.

Those video ads — in which unidentified spokespeople thumb through a newspaper to praise Trump, peddle conspiracy theories about the “Deep State,” and criticize “fake news” media — strike a familiar tone in the online conservative news ecosystem. The Epoch Times looks like many of the conservative outlets that have gained followings in recent years.

But it isn’t.

Behind the scenes, the media outlet’s ownership and operation is closely tied to Falun Gong, a Chinese spiritual community with the stated goal of taking down China’s government.

It’s that motivation that helped drive the organization toward Trump, according to interviews with former Epoch Times staffers, a move that has been both lucrative and beneficial for its message.

Former practitioners of Falun Gong told NBC News that believers think the world is headed toward a judgment day, where those labeled “communists” will be sent to a kind of hell, and those sympathetic to the spiritual community will be spared. Trump is viewed as a key ally in the anti-communist fight, former Epoch Times employees said.

In part because of that unusual background, The Epoch Times has had trouble finding a foothold in the broader conservative movement.

“It seems like an interloper — not well integrated socially within the movement network, and not terribly well-circulating among right-wingers,” said A.J. Bauer, a visiting professor of media, culture and communication at New York University, who is part of an ongoing study in which he and his colleagues interview conservative journalists.

“Even when discussing more fringe-y sites, conservative journalists tend to reference Gateway Pundit or Infowars,” Bauer said. “The Epoch Times doesn’t tend to come up.”

That seems to be changing.

Before 2016, The Epoch Times generally stayed out of U.S. politics, unless they dovetailed with Chinese interests. The publication’s recent ad strategy, coupled with a broader campaign to embrace social media and conservative U.S. politics — Trump in particular — has doubled The Epoch Times’ revenue, according to the organization’s tax filings, and pushed it to greater prominence in the broader conservative media world.

Started almost two decades ago as a free newspaper and website with a stated mission to “provide information to Chinese communities to help immigrants assimilate into American society,” The Epoch Times now wields one of the biggest social media followings of any news outlet.

In April, at the height of its ad spending, videos from the Epoch Media Group, which includes The Epoch Times and digital video outlet New Tang Dynasty, or NTD, combined for around 3 billion views on Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, ranking 11th among all video creators across platforms and outranking every other traditional news publisher, according to data from the social media analytics company Tubular.

That engagement has made The Epoch Times a favorite of the Trump family and a key component of the president’s re-election campaign. The president’s Facebook page has posted Epoch Times content at least half a dozen times this year— with several articles written by members of the Trump campaign. Donald Trump Jr. has tweeted several of their stories, too.

In May, Lara Trump, the president’s daughter-in-law, sat down for a 40-minute interview in Trump Tower with the paper’s senior editor. And for the first time, The Epoch Times was a main player at the conservative conference CPAC this year, where it secured interviewswith members of Congress, Trump Cabinet members and right-wing celebrities.

At the same time, its network of news sites and YouTube channels has made it a powerful conduit for the internet’s fringier conspiracy theories, including anti-vaccination propaganda and QAnon, to reach the mainstream.

Despite its growing reach and power, little is publicly known about the precise ownership, origins or influences of The Epoch Times.

The outlet’s opacity makes it difficult to determine an overall structure, but it is loosely organized into several regional tax-free nonprofits. The Epoch Times operates alongside the video production company, NTD, under the umbrella of The Epoch Media Group, a private news and entertainment company whose owner executives have declined to name, citing concerns of “pressure” that could follow.

The Epoch Media Group, along with Shen Yun, a dance troupe known for its ubiquitous advertising and unsettling performances, make up the outreach effort of Falun Gong, a relatively new spiritual practice that combines ancient Chinese meditative exercises, mysticism and often ultraconservative cultural worldviews. Falun Gong’s founder has referred to Epoch Media Group as “our media,” and the group’s practice heavily informs The Epoch Times’ coverage, according to former employees who spoke with NBC News.

Executives at The Epoch Times declined to be interviewed for this article, but the publisher, Stephen Gregory, wrote an editorial in response to a list of emailed questions from NBC News, calling it “highly inappropriate” and part of an effort to “discredit” the publication to ask about the company’s affiliation with Falun Gong and its stance on the Trump administration.

Interviews with former employees, public financial records and social media data illustrate how a secretive newspaper has been able to leverage the devoted followers of a reclusive spiritual leader, political vitriol, online conspiracy theories and the rise of Trump to become a digital media powerhouse that now attracts billions of views each month, all while publicly denying or downplaying its association with Falun Gong.

Behind the times

In 2009, the founder and leader of Falun Gong, Li Hongzhi, came to speak at The Epoch Times’ offices in Manhattan. Li came with a clear directive for the Falun Gong volunteers who comprised the company’s staff: “Become regular media.”

The publication had been founded nine years earlier in Georgia by John Tang, a Chinese American practitioner of Falun Gong and current president of New Tang Dynasty. But it was falling short of Li’s ambitions as stated to his followers: to expose the evil of the Chinese government and “save all sentient beings” in a forthcoming divine battle against communism.

Roughly translated by the group as “law wheel exercise,” Falun Gong was started by Li in 1992. The practice, which combines bits of Buddhism and Taoism, involves meditation and gentle exercises and espouses Li’s controversial teachings.

“Li Hongzhi simplified meditation and practices that traditionally have many steps and are very confusing,” said Ming Xia, a professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York who has studied Falun Gong. “Basically it’s like fast food, a quickie.”

Li’s teachings quickly built a significant following — and ran into tension with China’s leaders, who viewed his popularity as a threat to the communist government’s hold on power.

In 1999, after thousands of Li’s followers gathered in front of President Jiang Zemin’s compound to quietly protest the arrest of several Falun Gong members, authorities in China banned Falun Gong, closing teaching centers and arresting Falun Gong organizers and practitioners who refused to give up the practice. Human rights groups have reported some adherents being tortured and killed while in custody.

The crackdown elicited condemnation from Western countries, and attracted a new pool of followers in the United States, for whom China and communism were common adversaries.

“The persecution itself elevated Li’s status and brought tremendous media attention,” Ming said.

It has also invited scrutiny of the spiritual leader’s more unconventional ideas. Among them, Li has railed against what he called the wickedness of homosexuality, feminism and popular music while holding that he is a god-like figure who can levitate and walk through walls.

Li has also taught that sickness is a symptom of evil that can only be truly cured with meditation and devotion, and that aliens from undiscovered dimensions have invaded the minds and bodies of humans, bringing corruption and inventions such as computers and airplanes. The Chinese government has used these controversial teachings to label Falun Gong a cult. Falun Gong has denied the government’s characterization.

The Epoch Times provided Li with an English-language way to push back against China — a position that would eventually dovetail with Trump’s election.

In 2005, The Epoch Times released its greatest salvo, publishing the ”Nine Commentaries, ” a widely distributed book-length series of anonymous editorials that it claimed exposed the Chinese Communist Party’s “massive crimes” and “attempts to eradicate all traditional morality and religious belief.”

The next year, an Epoch Times reporter was removed from a White House event for Chinese President Hu Jintao after interrupting the ceremony by shouting for several minutes that then-President George W. Bush must stop the leader from “persecuting Falun Gong.”

But despite its small army of devoted volunteers, The Epoch Times was still operating as a fledgling startup.

Ben Hurley is a former Falun Gong practitioner who helped create Australia’s English version of The Epoch Times out of a living room in Sydney in 2005. He has written about his experience with the paper and described the early years as “a giant PR campaign” to evangelize about Falun Gong’s belief in an upcoming apocalypse in which those who think badly of the practice, or well of the Chinese Communist Party, will be destroyed.

Hurley, who wrote for The Epoch Times until he left in 2013, said he saw practitioners in leadership positions begin drawing harder and harder lines about acceptable political positions.

“Their views were always anti-abortion and homophobic, but there was more room for disagreements in the early days,” he said.

Hurley said Falun Gong practitioners saw communism everywhere: former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, movie star Jackie Chan and former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan were all considered to have sold themselves out to the Chinese government, Hurley said.

This kind of coverage foreshadowed the news organization’s embrace of conspiracy theories like QAnon, the overarching theory that there is an evil cabal of “deep state” operators and child predators out to take down the president.

“It is so rabidly pro-Trump,” Hurley said, referring to The Epoch Times. Devout practitioners of Falun Gong “believe that Trump was sent by heaven to destroy the Communist Party.”

A representative for Li declined an interview request. Li lives among hundreds of his followers near Dragon Springs, a 400-acre compound in upstate New York that houses temples, private schools and quarters where performers for the organization’s dance troupe, Shen Yun, live and rehearse, according to four former compound residents and former Falun Gong practitioners who spoke to NBC News.

They said that life in Dragon Springs is tightly controlled by Li, that internet access is restricted, the use of medicines is discouraged, and arranged relationships are common. Two former residents on visas said they were offered to be set up with U.S. residents at the compound.

Tiger Huang, a former Dragon Springs resident who was on a U.S. student visa from Taiwan, said she was set up on three dates on the compound, and she believed her ability to stay in the U.S. was tied to the arrangement.

“The purpose of setting up the dates was obvious,” Huang said. Her now-husband, a former Dragon Springs resident, confirmed the account.

Huang said she was told by Dragon Springs officials her visa had expired and was told to go back to Taiwan after months of dating a nonpractitioner in the compound. She later learned that her visa had not expired when she was told to leave the country.

Campaign season

By 2016, The Epoch Times Group appeared to have heeded the call from Li to run its operation more like a typical news organization, starting with The Epoch Times’ website. In March, the company placed job ads on the site Indeed.com and assembled a team of seven young reporters otherwise unconnected to Falun Gong. The average salary for the new recruits was $35,000 a year, paid monthly, according to former employees.

Things seemed “strange,” even from the first day, according to five former reporters who spoke with NBC News — four of whom asked for anonymity over concerns that speaking negatively about their experience would affect their relationship with current and future employers.

As part of their orientation, the new reporters watched a video that laid out the Chinese persecution of Falun Gong followers. The publisher, Stephen Gregory, also spoke to the reporters about his vision for the new digital initiative. The former employees said Gregory’s talk framed The Epoch Times as an answer to the liberal mainstream media.

Their content was to be critical of communist China, clear-eyed about the threat of Islamic terrorism, focused on illegal immigration and at all times rooted in “traditional” values, they said. This meant no content about drugs, gay people or popular music.

The reporters said they worked from desks arranged in a U-shape in a single-room office that was separated by a locked door from the other staff members who worked on the paper, dozens of Falun Gong volunteers and interns. The new recruits wrote up to five news stories a day in an effort to meet a quota of 100,000 page views, and submitted their work to a handful of editors — a team of two Falun Gong-practicing married couples.

“Slave labor may not be the right word, but that’s a lot of articles to write in one day,” one former employee said.

It wasn’t just the amount of writing but also the conservative editorial restrictions that began to concern some of the employees.

“It’s like we were supposed to be fighting so-called liberal propaganda by making our own,” said Steve Klett, who covered the Trump campaign for The Epoch Times as his first job in journalism. Klett likened The Epoch Times to a Russian troll farm and said his articles were edited to remove outside criticism of Trump.

“The worst was the Pulse shooting,” Klett said, referring to the 2016 mass shooting in which 50 people including the gunman were killed at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. “We weren’t allowed to cover stories involving homosexuality, but that bumps up against them wanting to cover Islamic terrorism. So I wrote four articles without using the word gay.”

Klett said that the publication also began to skew in favor of Trump, who had targeted China on the campaign trail with talk of a trade war.

“I knew I had to forget about all the worst parts of Trump,” Klett said.

Klett, however, would not end up having to cover the Trump administration. Eight days before the election, the team was called together and fired as a group.

“I guess the experiment was over,” a former employee said.

The content

The Epoch Times, digital production company NTD and the heavily advertised dance troupe Shen Yun make up the nonprofit network that Li calls “our media.” Financial documents paint a complicated picture of more than a dozen technically separate organizations that appear to share missions, money and executives. Though the source of their revenue is unclear, the most recent financial records from each organization paint a picture of an overall business thriving in the Trump era.

The Epoch Times brought in $8.1 million in revenue in 2017 — double what it had the previous year — and reported spending $7.2 million on “printing newspaper and creating web and media programs.” Most of its revenue comes from advertising and “web and media income,” according to the group’s annual tax filings, while individual donations and subscriptions to the paper make up less than 10 percent of its revenue.

New Tang Dynasty’s 2017 revenue, according to IRS records, was $18 million, a 150 percent increase over the year before. It spent $16.2 million.

That exponential growth came around the same time The Epoch Times expanded its online presence and increased its ad spending, honing its message on two basic themes: enthusiastic support for Trump’s agenda, and the exposure of what the publication claims is a labyrinthian, global conspiracy led by Clinton and former President Barack Obama to tear down Trump. One such conspiracy theory, loosely called “Spygate,” has become a common talking point for Fox News host Sean Hannity and conservative news websites like Breitbart.

The paper’s “Spygate Special Coverage” section, which frequently sits atop its website, theorizes about a grand, yearslong plot in which former Obama and Clinton staffers, a handful of magazines and newspapers, private investigators and government bureaucrats plan to take down the Trump presidency.

In his published response, publisher Gregory said the media outlet’s ads “have no political agenda.”

While The Epoch Times usually straddles the line between an ultraconservative news outlet and a conspiracy warehouse, some popular online shows created by Epoch Times employees and produced by NTD cross the line completely, and spread far and wide.

One such show is “Edge of Wonder,” a verified YouTube channel that releases new NTD-produced videos twice every week and now has more than 33 million views. In addition to claims that alien abductions are real and the drug epidemic was engineered by the “deep state,” the channel pushes the QAnon conspiracy theory, which falsely posits that the same “Spygate” cabal is a front for a global pedophile ring being taken down by Trump.

One QAnon video, titled “#QANON – 7 facts the MEDIA (MSM) Won’t Admit” has almost 1 million views on YouTube. Other videos in the channel’s QAnon playlist, which include videos about 9/11 conspiracy theories and one titled “13 BLOODLINES & their Diabolical End Game,” gained hundreds of thousands of views each.

Travis View, a researcher and podcaster who studies the QAnon movement, said The Epoch Times has sanitized the conspiracy theory by pushing Spygate, which drops the wildest and more prurient details of QAnon while retaining its conspiratorial elements.

“QAnon is highly stigmatized among people trying to push the Spygate message. They know how toxic QAnon is,” View said. “Spygate leaves out the spiritual elements, the child sex trafficking, but it’s certainly integral to the QAnon narrative.”

Gregory denied any connection with “Edge of Wonder,” writing in a statement that his organization was “aware of the entertainment show,” but “is in no way connected with it.”

But The Epoch Times has itself published several credulous reportson QAnon and for years, the webseries hosts Rob Counts and Benjamin Chasteen were employed as the company’s creative director and chief photo editor, respectively. In August 2018, six months after the creation of “Edge of Wonder,” Counts tweeted that he still worked for Epoch Times. Counts and Chasteen did not respond to an email seeking clarification on their roles.

Meanwhile The Epoch Times has promoted “Edge of Wonder” content in dozens of Facebook posts, still visible on its official Facebook page. That page is currently topped with a pinned ad for its Trump coverage that reads, “Where can you get real news that doesn’t push any hidden agendas?”